The Spanish Inquisition, which lasted from 1478 to 1834, was created to expose and weed out supposed heresy against the Catholic Church — including blasphemy and witchcraft. Approximately 150,000 people were prosecuted, including thousands of clergy members, while nearly 5,000 people were executed.

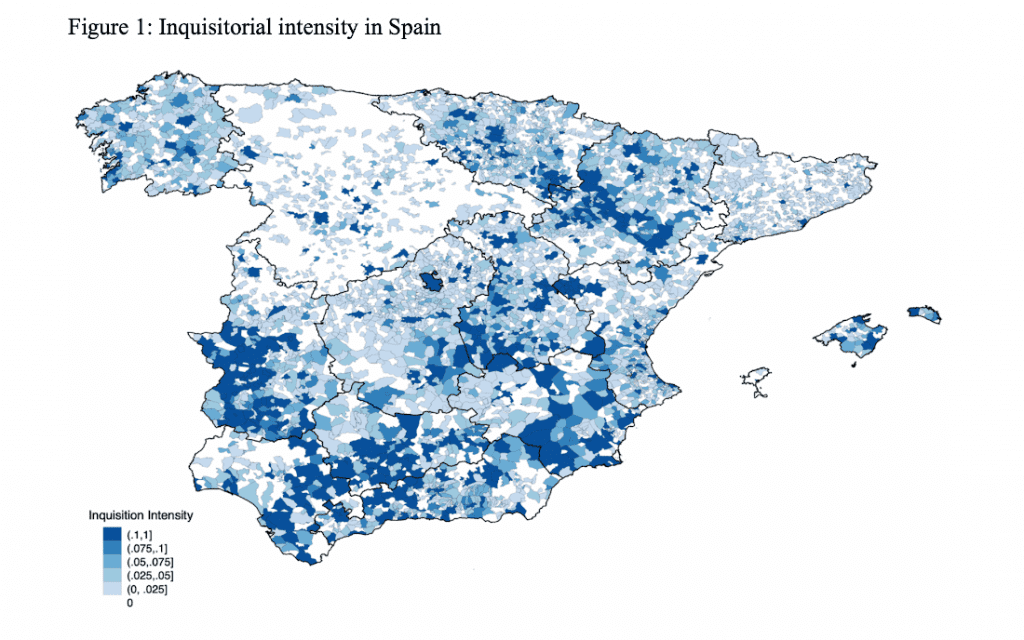

Of all the territories in which the Inquisition took place — think of them like congressional districts today — 16 of them were in modern-day Spain.

For researchers Mauricio Drelichman, Jordi Vidal-Robert, and Hans-Joachim Voth, that led to an interesting question: Is it possible to see how the areas once ravaged by the Inquisition are doing compared to the parts of Spain that were not subject to it?

In other words, does the Spanish Inquisition have a tangible, measurable, modern impact?

They found out that it absolutely does, writing in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition to still matter today — but it does.”

From Imperial Rome to North Korea, religious persecution entwined with various degrees of totalitarian control has caused conflict and bloodshed for millennia. In this paper, we ask — can it have repercussions long after the persecution has ceased? Using new data on the Spanish Inquisition, we show that municipalities where the Spanish Inquisition persecuted more citizens incomes are lower, trust is lower, and education is markedly lower than in comparable other towns and cities.

How did they come to that conclusion? They looked at tens of thousands of individual records of Inquisition trials from the various courts in what is now Spain and connected them with both opinion surveys (from the Spanish Center for Sociological Research) and a variety of socioeconomic indicators.

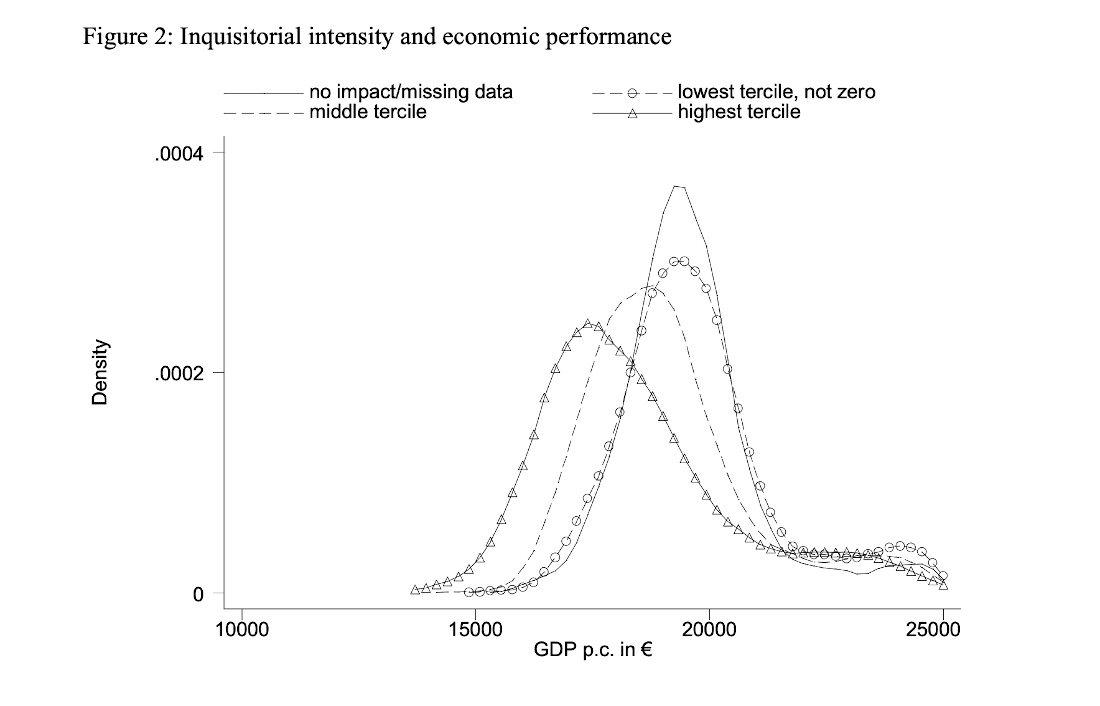

Consider the economy. The chart below shows how parts of Spain affected by the Inquisition are doing today in terms of GDP per capita. If the peak of a curve is toward the right side of the chart, that’s good! It means more people are making more money, generally speaking.

See the solid line that rises above the others? That represents the parts of Spain that were not impacted at all by the Inquisition. It’s tall and shifted to the right, which is what you want to see.

Now look at the line with the circles on it. It’s not as tall, but still, not bad! The GDP is still decent.

But that line with the triangles on it is much shorter and shifted to the left. Those are the parts of Spain where the Inquisition was most active.

That’s one indication that the Inquisition directly impacts today’s economy even though it ended roughly two centuries ago.

Where the Inquisition struck with highest intensity (top tercile), the level of economic activity in Spain today is sharply lower. Magnitudes are large: In places with no persecution, median GDP per capita was 19,450€; where the Inquisition was active in more than 3 years out of 4, it is below 18,000€. For a municipality with average GDP per capita, a one standard deviation increase in inquisitorial intensity (0.058) is associated with a 330€ decline in average annual income per capita, while going from the 75% to the 99% percentile reduces income by 1,428€. Our estimates imply that, had Spain not suffered from the Inquisition, its annual national production today would be 4.1% higher — or 811€ for every man, woman, and child.

The moral of the story is clear: Repressive faith-based regimes like the Inquisition can have long-term negative impacts.

… Areas where the Inquisition persecuted more citizens are markedly poorer today. We also present evidence that the mechanism behind the long-term detrimental impact of the Inquisition operated through lower trust and education. While we cannot establish that these relationships are causal in a strict sense, historical indicators of religiosity and wealth show that the areas targeted by the Inquisition were not poor or particularly religious in the early modern period.

The negative effect of the Inquisition suggests that adverse shocks at a critical juncture can trap societies in permanently low equilibria, where high local conflict, low education and limited trust lead to low income, with the risk of undermining social capital and trust still further…

Religion-inspired persecution isn’t just bad in the present-day. The ramifications of letting religious bigotry flourish can hurt people for generations to come. Better to fight it now before it affects the future.

If you prefer reading a simplified summary of the paper, here’s one written by the researchers.

(Featured image via Shutterstock. Thanks to Andrey for the link)

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."