Students at North Carolina’s Lake Norman Charter School can continue to read a controversial book of poetry in English class, thanks to this week’s ruling from a federal district court.

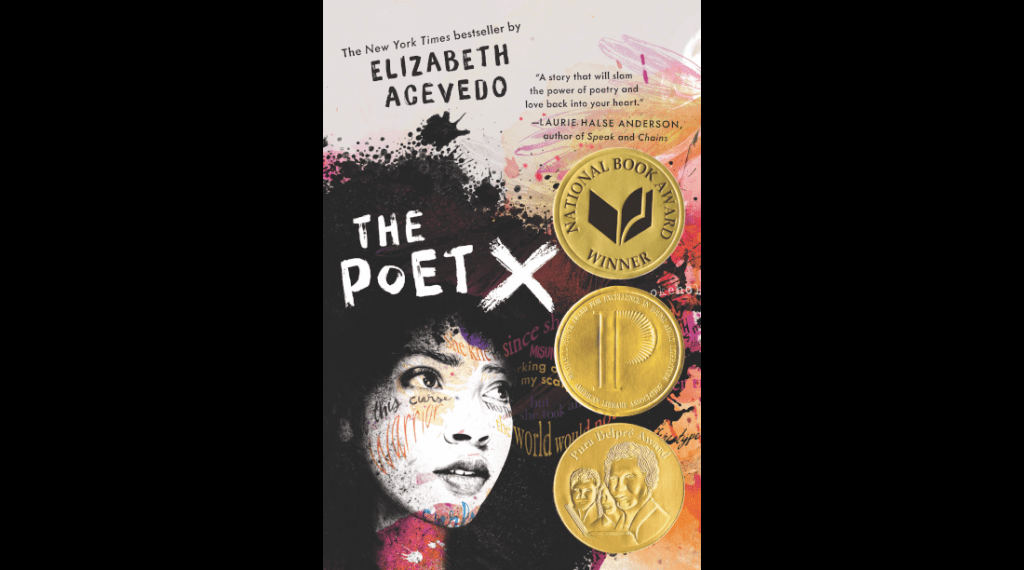

The book in question is The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, a coming-of-age story about an Afro-Latina poet facing familial pressure to conform to cultural and religious expectations. The lawsuit arose after parents claimed the book was anti-Catholic as a result of the protagonist’s expressed doubts about her family’s religion.

The court’s refusal to apply a temporary injunction — which would’ve prevented the book’s use in the 9th-grade classroom until a ruling could be made — meant that teachers could use the book in the classroom through 2020, making the question moot for their son’s cohort of learners.

But this is a separate ruling that will affect future students’ ability to study the book in class, and teachers’ freedom to include it in the curriculum.

The initial objection came from parents John and Robin Coble, who argued that the book’s exploration of religious doubt and pressure amounted to “a frontal assault on Christian beliefs and values,” therefore violating their child’s First Amendment rights as well as their own rights as parents.

In this latest decision, Judge Max O. Cogburn Jr., notes that “to the Cobles, the case begins and ends with LNC’s decision to teach a book with the anti-Christian content of The Poet X.” That’s not enough to make it a First Amendment violation, though:

It is not the content of the book or LNC’s decision to teach the book that is the relevant legal issue. Rather, what matters is how LNC uses the book in the classroom. As the Supreme Court has made clear, even the Bible can be taught for particular purposes in public school without running afoul of the Establishment Clause.

In a case like this, it’s not enough to be able to demonstrate that a book contains criticism or hostility towards a given religion. That’s easy: The book’s narrator criticizes her family’s Catholic religion and expresses skepticism about its claims.

To prove their case, the plaintiffs also need to demonstrate with facts and evidence that the school is endorsing the narrator’s criticisms or requiring students to agree with them. In that, Cogburn notes, the Cobles and their legal team fall short, making no attempt to document or present facts about the classroom experience:

The Cobles make no allegations as to the specifics of LNC’s use of The Poet X in the classroom. They also do not allege specific allegations about how the school’s decision to teach the book inhibited their son’s religious rights… The Complaint contains nothing regarding (a) how LNC planned to use the book; (b) [student]’s personal beliefs; or (c) how LNC’s specific use of the book would unduly burden his religious practices.

Cogburn brings up an interesting point there: For all that Mr. and Mrs. Coble insist that the book is an affront to their Christian values, no mention is made of their son’s feelings and opinions in all this. Does he feel like his free exercise of religion has been violated? Does the book even challenge his personal beliefs at all? His parents have spoken for him throughout the lawsuit — and while that’s appropriate in legal cases involving minors, the case fails to demonstrate any distress or conflict Coble the Younger might experience as a result of Acevedo’s challenges to the Catholic faith.

Make no mistake: That discomfort would not be enough to justify removing the book from the classroom. But it’s an elision that brings up questions. Perhaps the Cobles’ fears grow out of a suspicion that their son might well agree with the narrator when she describes Jesus Christ as “a friend I just don’t think I need anymore.”

We can’t know how the younger Cobles feels about all this, because his parents are treating his perspective as an automatic extension of their own. In essence, they believe they have a right to order the world around them such that their child(ren) will never be exposed to anything that causes them to ask questions.

The North Carolina federal district court doesn’t agree.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."