Remember how Time magazine editors have been known to misrepresent atheists?

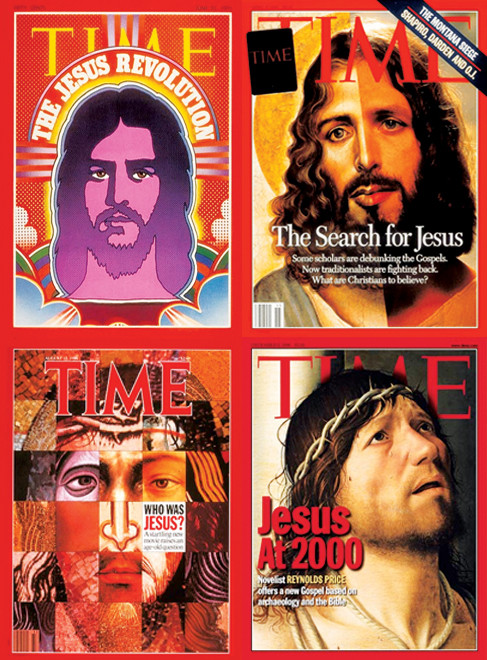

I don’t know — maybe that’s considered smart business at a publication that sees its sales spike with each Jesus cover.

Whatever the case, Time is at it is again.

In the “Science and Space” section (so you know it’s true!), the magazine offers this.

Headline:

Why There Are No Atheists at the Grand Canyon

Intro:

All it takes is a little awe to make you feel religious

Senior Editor Jeffrey Kluger‘s commentary (in the companion video):

“It’s hard to be an atheist when you’re looking at the Grand Canyon.”

Is it really now? What kind of Oprah-esque fatuity is this?

I’ve been to the Grand Canyon. I’ve traveled to other awe-inspiring locations, too — from South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to the French and Italian coasts, and from the inlands of China to the jungles of Kalimantan. My house happens to be on an island in the middle of Maine’s Acadia National Park, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. A pair of eagles often dive-bombs for fish in the fjord whose shoreline is 25 yards from my front door. Our night skies, unpolluted by city lights, can make you weep for all their clarity, vastness, and mystery.

This is to say, I know awe.

And yet, I don’t know a single atheist who has ever taken in the sights that I have (or similar ones) and became an ardent believer in a divine Creator. When gazing up at the sky, atheists are more likely to want to be a part of this

than a part of this.

than a part of this.

Provably, then, there are atheists at the Grand Canyon. Not a few either, I’m sure.

Provably, then, there are atheists at the Grand Canyon. Not a few either, I’m sure.

Kluger bases his skewed piece on a study by two psychologists, Piercarlo Valdesolo of Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California, and Jesse Graham of the University of Southern California. They conducted an interesting experiment.

Subjects were primed with one of several types of video clip: a 1959 TV interview conducted by newsman Mike Wallace; light scenes of animals behaving in funny or improbable ways; or sweeping scenes of nature — mountains, canyons, outer space — from a BBC documentary. Some of the subjects were also shown more surreal, computer-generated scenes: lions flying out of buildings, a waterfall flowing through a city street.

Quick aside: I’m pretty sure I’ve seen those BBC images. I own both Planet Earth and Life on Bluray. Jaw-dropping though both productions are, they didn’t give me any religious stirrings either.

And let’s please note the irony-filled fact that few men have spent as much time looking at the gorgeous BBC footage as its narrator, David Attenborough, who is (get this) an agnostic. A decade ago, Attenborough gave us this trenchant observation:

“When creationists talk about God …, they always instance hummingbirds, or orchids, sunflowers and beautiful things. But I tend to think instead of a parasitic worm that is boring through the eye of a boy sitting on the bank of a river in West Africa, that’s going to make him blind. Are you telling me that the God you believe in, who you also say is an all-merciful God, who cares for each one of us individually, are you saying that God created this worm that can live in no other way than in an innocent child’s eyeball? Because that doesn’t seem to me to coincide with a God who’s full of mercy.“

Anyway, back to the research that inspired Kluger and his Time article. After watching the different types of video footage,

The subjects were all then administered one or more questionnaires. One asked them straightforwardly, “To what extent did you experience awe while watching the video clip?” Another asked them to respond to questions about their belief in a universe that either does or doesn’t “unfold according to God’s or some other nonhuman entity’s plan.” Another asked them about their tolerance for uncertainty or ambiguity.

While atheists on the one hand and people of deep faith on the other don’t move off their baseline positions much (though even they have periods of doubt), the rest of us are more influenced by experiences. Thus, the subjects who had felt more wonder or awe when they’d watched the grand or surreal videos would score higher on belief in a universe that proceeds according to a master plan than subjects who saw lighter or more prosaic clips.

Note how completely different this is from the asinine assertion in the headline that “there are no atheists at the Grand Canyon,” and from the equally dumbfounding web-page title that says “Awe Makes You Religious.”

It’s easy, though, to agree with this finding of Graham’s and Valdesolo’s:

All awe contains a slight element of fear or at least vulnerability, and the sooner we have an explanation for what it is we’re seeing and how it came to be, the more reassured we are. Think how often we comfort a child who’s just been frightened by something new and scary with an explanation like, “It’s just thunder” or lightning or a blimp or a parade balloon.

This is exactly what faith is when it springs from awe: the childlike impulse to embrace the simplest explanation that will make our fears and our sense of insignificance go away. On that count, religion easily scores a twofer: it explains where stuff came from (God made it), and it reassures us that we matter a great deal (because God loves each and every one of us). A more inquisitive and deeper investigation into the hows and wherefores of the universe requires a much higher tolerance for uncertainty, and for the fact that our collective human knowledge improves slowly, each answer spawning new questions. It’s plain to see which of these two options is superficially more attractive. Subscribing to the scientific worldview is a lot of work compared to latching on to the first feelgood explanation that tickles your fancy.

Kluger ends by once again injecting his bias into the article:

Awe trumps empiricism — and like it or not too, we’d probably be a poorer species if it didn’t.

Really? We’d be a poorer species if we’d resolutely decided a thousand years ago that we would collectively embrace our natural awe as an engine for scientific progress? Are we better off now for having spent much of the past millennium on our knees, stifling our curiosity so as not to offend God? And when we did venture out, did we do ourselves any favors by engaging in centuries of zealous skull-bashing over whose religion is truer?

I very much doubt it. It all comes down to these words of Carl Sagan, the late astrophysicist and science popularizer who made a career out of voicing awe, and who nonetheless never saw the need for religion.

It is far better to grasp the universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.

And that’s the god’s honest truth.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."