Randy R. Potts comes from a famous family. His grandfather was the pioneering televangelist Oral Roberts. His uncle, Richard Roberts, ran the conservative Christian university that bears Oral’s name until 2007, when a scandal forced him to resign. Richard continues to run the Oral Roberts Evangelical Association and appear at revivals and on evangelical TV stations.

But Potts is not a part of that world. He is openly gay and describes himself as “godless.” And he is not the first member of the Roberts clan to choose a different path, either. In a letter featured in the book It Gets Better: Coming Out, Overcoming Bullying, and Creating a Life Worth Living, he tells the sad story of Oral’s oldest son, his uncle Ronnie.

My uncle, Ronald David Roberts, was born in 1945, the oldest son of the late televangelist, Oral Roberts, my grandfather. My Uncle Ronnie, like me, was gay. He wrote in letters, published after his death, that he “came out” in high school, but only to close friends and family, including his father. His father, Oral Roberts, was the first televangelist, and likely the most famous faith-healer since Jesus Christ, with a worldwide audience in the hundreds of millions. He did not want a gay son. Oral’s anti-homosexual rants were so vehement that they can still be found on YouTube, forty years later. In his thirties, six months after getting divorced and coming out, my Uncle Ronnie died, on June 10th, 1982, by a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the heart.

I have lived in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the site of Oral Roberts University and the ministries associated with it, for the majority of my life. My grandfather, my father, and one of my uncles worked at the school in the 1980s. One of my sisters received two ORU degrees along with her husband. I socialized with some of her college friends when he I was in high school. I heard all kinds of stories about the Roberts family growing up (few of them flattering), but this is one that I missed.

The news reports from 1982 about Ronald Roberts’ suicide do not mention his sexuality.

Roberts, 37, died from a single .25-caliber gunshot wound to the heart, Osage County Sheriff George Wayman said.

A passer-by found the Tulsa evangelist’s son slumped in his car, parked on an Osage County road about 15 miles northwest of Tulsa.

Wayman said the bullet wound that killed Roberts appeared to be self-inflicted. He said no note or letter was discovered with the body, but “two or three” notes were found in Roberts’ apartment at 4309 S. Owasso Ave.

Wayman declined to discuss in detail the contents of the notes. But he said although none of the notes mentioned suicide, they left the impression Roberts intended to take his own life.

Oral Roberts claimed that the his son’s service in Vietnam changed him, and that the tragedy made him “more determined than ever” to pursue his ministry.

In an essay published in This Land, a bi-weekly alternative newspaper in Tulsa, Potts recounts how difficult it was to grow up gay and fearful of damnation. He writes about being a 7th grader in 1987, when Oral made national news by holding a vigil in the Prayer Tower on Campus, claiming that if he did not raise $8 million for medical missions, “God will call me home.”

I was twelve, my grandfather was in a tower, and I was worried about the rapture, but I was also a seventh-grade gay kid in an evangelical Christian middle school, trying my best to develop crushes on girls. There was one girl I asked out every single day for a month and she said no every time, until it became a sort of joke and I asked her the way I scratched my nose, that is, quickly and sharply. And why did I ask her every day? Because my best friend at the time, a boy I haven’t seen since 1988 but still remember his full name and telephone number… had kissed this girl. I think I was hoping that, if I kissed her too, I would somehow get some of his germs. Or something like that. None of this was conscious, but looking back it’s the only way I can make sense of it. Because, looking back, while I romanced the girls I ended up being nothing but a pest, stealing their lunch bags, undoing their bra as a joke, etc.–all I was really interested in were boys.

Potts adult life followed a pattern familiar to many gay men raised in religious environments. He met a nice woman, married her at a young age, and had children with her. He was only postponing a full acknowledgement of the truth, as he explains in the It Gets Better letter.

It all started for me one summer afternoon when I was twenty-seven years old, and I stood in my kitchen and said to myself, out loud, that I was gay. It was the most liberating feeling I’ve ever had, and for the next three days I was on top of the world. But then reality came crashing down on me — I was married, with children, and I didn’t know what being gay would mean in terms of my family, my wife, my children. It was a horrible place to be. It took a few more years of being scared to death and going to two different therapists before I finally decided that the best thing for everyone involved was for me to get divorced and come out. I had been suicidal for years, and I eventually realized that my children needed a father who wanted to live, who looked forward to tomorrow, and the only way I could be that man was to get divorced and come out.

That’s when I started writing my letter to my uncle, because I felt like he was the only one who would understand. My parents didn’t understand, most of my friends didn’t understand — it was something I didn’t know how to explain, so I started writing.

He came close to ending his life the way his Uncle Ronnie, who was also divorced and a father of young children, did. But he managed to make a better life for himself, and now he’s doing admirable work trying to get his message out to the many gays and lesbians in evangelical communities.

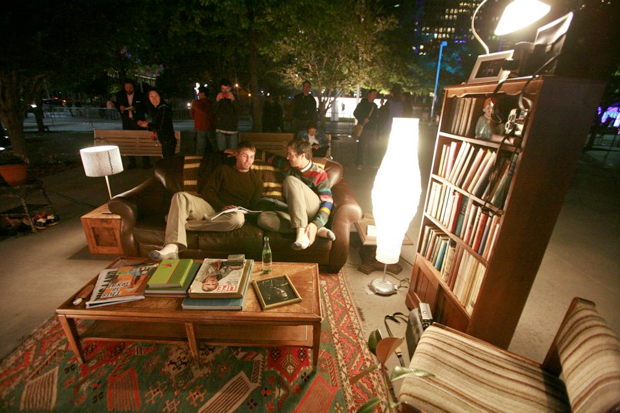

He now lives in Dallas and hopes to write a book about his experiences (I know I would read it). He and his boyfriend, Keaton Johnson, are currently taking an installation called “The Gay Agenda” on tour. It’s designed to show Americans just how mundane and normal the lives of gay couples can be. It consists of Potts and Johnson sitting on a couch, watching TV and vacuuming.

It would easier for preachers to denounce the idea of homosexuality as something that happens somewhere else, in godless coastal cities, by people that the churchgoers of middle-America are unlikely to ever meet. Potts is helping change that by forcing Christians to acknowledge that gays and lesbians are born in places like Texas and Oklahoma, into even the most devout families. While some pastors speak out against homosexuality using falsehoods or a Holy Book, Potts is showing them an image of gay couples consisting of two men on a couch, having a pleasant conversation, sharing love and companionship. In other words, they’re really not unlike the rest of us.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."