The New Yorker recently published a think piece on the future of evangelicalism, specifically discussing two big questions: Is the millennial crowd diverging from the beliefs of their parents? And how much have politics played a role in that divergence?

Reporting on a service at Block Church in Philadelphia, Eliza Griswold writes,

At the Block Church, black, white, and Latino evangelicals were worshipping together, which is still a rare sight. During the past decade, evangelicalism has grown more diverse: as the number of white believers has declined, the Latino evangelical population has increased dramatically.

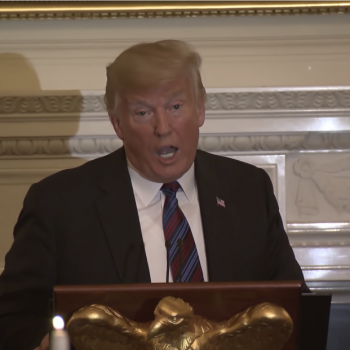

Even so, eighty-six per cent of evangelical churches remain segregated, a statistic from the National Congregations Study at Duke University, which Robert P. Jones cites in his book “The End of White Christian America.” From a distance, evangelicalism can appear culturally monolithic—nearly eighty per cent of white evangelicals support President Trump, according to the Public Religion Research Institute — but many young evangelicals are more diverse, less nationalistic, and more heterodox in their views than older generations. Believing that being a Christian involves recognizing the sanctity of all human beings, they support Black Lives Matter and immigration reform, universal health care and reducing the number of abortions, rather than overturning Roe v. Wade.

It’s not exactly news that each subsequent generation is a tad more liberal than its predecessors. But the presidency of Donald Trump has unleashed an unprecedented amount of open, unabashed racism and bigotry toward minorities. The loudest voices preaching this toxicity tend to belong to evangelical Christians. Millennials, who are more likely to know LGBTQ people personally, and suffer the brunt of an expensive healthcare system while dealing with student loan debt, are taking notice. And they aren’t too impressed by the hypocrisy.

One evening this summer at the Block Church, I met Julio Colón-Laboy, a clean-cut and soft-spoken twenty-year-old who was manning a card table outside the Clef Club with a plate of chocolate-chip cookies. He had a sign-up sheet for a small discussion group, which would be reading the Book of James verse by verse together all summer.

…

In 2014, the Block Church opened in his neighborhood, and he joined the congregation. Since then, he has graduated from high school and received a scholarship to the University of Vermont. It wasn’t easy to be an evangelical Christian up in Yankee Burlington. “When I say, ‘Hey, I’m a Christian,’ people think I have guns on me that no one can take and that I picket outside abortion clinics,” he told me. “As a young Christian who cares about social justice, it breaks my heart to be lumped in with this identity.”

That identity Colón-Laboy speaks of may be a stereotype to some; an unfair caricature of what American Christianity looks like. And yet, within most stereotypes is a small grain of truth: that reputation isn’t wholly undeserved.

As a result, many young Christians are reconsidering the value of labels. They want to belong somewhere, but also don’t want to be permanently boxed:

Among younger Christians like Colón-Laboy, it isn’t unusual to oppose abortion but support immigration rights. Many are no longer willing to ally themselves categorically with either the right or the left. Instead, they challenge all kinds of ideas of identity and tribe. The separation of families at the border, however, coalesced young Christians around a new level of outrage.

“It’s wicked and absolutely evil for this regime to treat children like they are disposable,” Ekemini Uwan, a thirty-six-year-old public theologian who recently completed a Masters of Divinity Studies at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, told me. “And I’m supposed to believe that Trump is pro-life?” For Uwan, who became a born-again Christian while at California State University, Northridge, in Southern California, being pro-life, rather than anti-abortion, also involves protecting people’s rights to health care and education. “If you’re weeping for the child who has been aborted, you should be weeping for Trayvon Martin and black mothers in Flint who are experiencing miscarriages as a result of lead poisoning,” she told me.

The new trend, according to Griswold, is for young Christians to identify as theologically conservative, not politically conservative — believing this is the most authentic way to follow the teachings of Jesus. (As for abortion, they oppose it, but they’re also more likely to support access to contraception, sex education, and other known methods of reducing abortion rates.)

While young Christians may not be completely ditching the faith of their parents, it’s still clear that the practice of it looks different. That means the dominant strain of American Christianity will also change. They are intent to make it their own and embrace the nuance of complex topics that aren’t necessarily clear in Scripture. The typical black-and-white thinking we’ve long criticized is disappearing. As millennials realize that their identities are not strictly binary, so, too, is the way they view the world.

(Image via Shutterstock)

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."