On their website, Sophia Institute Press describes its wares as “faithful Catholic classics and new texts by the great enduring figures of the Catholic intellectual tradition.”

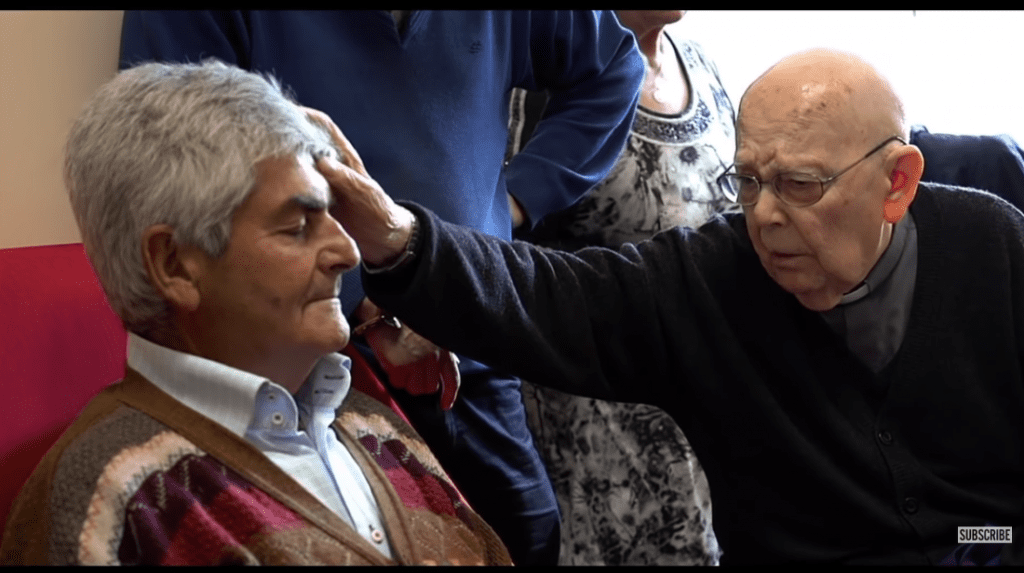

Father Gabriele Amorth, world-renowned exorcist, could hardly be called one of them.

His recent posthumous biography, The Devil Is Afraid of Me: The Life and Work of the World’s Most Famous Exorcist, describes a man who, at the peak of his faculties, performed upwards of 17 exorcisms per day while relying on his fellow priests to update him on world events in the space of a single shared meal.

Amorth seems almost proud when he brags about coasting through university without studying or attending classes, saying “they gave me the degree as a gift.”

The book may tout his expertise concerning the world of demons, but when it comes to the human world, the man comes across as profoundly incurious and frequently ill-informed.

Father Amorth died some years before the book’s publication, and as he emphasizes strongly in the book, the dead cannot come into contact with the living to write biographies. (Ghosts aren’t real, he insists; only demons are.) So the actual text was written and assembled by Father Marcello Stanzione, albeit with enough reprints of Amorth’s old interviews to earn the exorcist full author credit. In fact, while the book’s cover credits him as a lesser co-author to the dead priest, it’s the only place the press bothers to acknowledge his contribution.

Stanzione claims no hard feelings, though. In fact, he called Amorth “the figure of Christ the Healer” and identifies him as a prime candidate for canonization:

If you will pardon the audacity of my affection and admiration (and ignore the decree of Pope Urban VIII that asked the faithful to leave judgment on the matter to the Church), I must say that Father Amorth was a giant, a teacher, an example of greatness, and therefore a saint.

I’m not so sure.

Promotional materials for the book love to mention that Amorth credits himself with more than 60,000 exorcisms during his career, at that punishing pace of 17 per day. Elsewhere, he’s claimed as many as 160,000 (circa 2013). This assembly-line pace doesn’t leave a lot of room for proceeding cautiously. Amorth claims, therefore, to have used exorcism as a diagnostic tool, reasoning that “if a person has a need for an exorcism, fine; if not, the exorcism does no harm.”

But the process of exorcism seems like it could be extremely scary, potentially traumatic to the person undergoing it. Amorth is equivocal on the issue of consent, at times insisting he won’t exorcise someone without it, only to later argue in favor of presuming consent when someone refuses the rite:

These [non-consenting] persons wish to have the exorcisms; it is the demon that is impeding them from reaching the exorcist. In those cases, one can force the person, even with force, to accept the exorcism. It is necessary, however, to have the consent of the family.

It’s not hard to imagine how this could add up to a harmful outcome, even a legally actionable one. But Amorth never addresses that question, and if it ever came up, it’s been well and truly buried.

Ultimately, though, the question of whether someone needs an exorcism or not is unfalsifiable. Once a person is branded as demon-possessed, there’s no losing for priests like Father Amorth. If the exorcism doesn’t work, it could be God’s plan. It could also be the fault of the victim:

Sometimes there are impediments to grace: the difficulty of a sincere, heartfelt pardon; the difficulty of changing a lifestyle that is rooted in sin; the difficulty of breaking certain ties with the Evil One that require breaking off certain human ties: sinful friendships, rooted vices.

It’s a great way to never have to grapple with the question of whether an exorcism really does harm the person receiving it.

The Church has at least gestured at considering those questions, putting rules in place to control who may perform an exorcism, and how, and under what circumstances. But whether Father Amorth accepts those rules becomes increasingly muddy over the course of the book. Certainly Amorth is critical of the Church hierarchy, complaining of neglectful bishops and power-hungry careerists, even alluding to “members of satanic sects” within the Vatican power structure. (Even the fairly-deferential interviewer felt compelled to ask, “Excuse me, Father Gabriele, but how do you know?” The answer was vague, but at least partly involved demonic snitches.)

So does Amorth believe ordinary Catholics can perform exorcisms? He pays lip service to the official restrictions, explaining that only duly-appointed exorcists may practice the exorcism rite while offering would-be demon-fighters the option of saying a “prayer of liberation”: less formal, but “as effective as true and proper exorcisms.”

Now, don’t misunderstand: nobody here is blaming him for disrespecting the Vatican hierarchy. I don’t respect it much myself.

But Amorth’s writings and interviews emphasize the tradition of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, roughly the equivalent of Protestant Pentecostalism, with its emphasis on individual Christians being moved by the Holy Spirit to act in God’s name. Encourage enough people to act on their instincts and preconceptions, telling them it’s the prodding of their deity, and the potential for truly ugly outcomes is apparent.

Potential demoniacs can’t prove they’re not possessed. Their efforts to refuse are potential evidence of possession. And the duty to “liberate” them is in the hands of any believer.

These are the sorts of issues Father Gabriele Amorth never took the time to consider deeply during his long and extremely busy life. Perhaps it would have been better if he’d cut down his caseload by ten thousand or so, instead giving a bit of thought to the potential consequences of his beliefs.

(Screenshot via YouTube)

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."